1 August 2022 | Education and employment

Why challenging behaviour in schools could be masking vocabulary gaps

Behavioural issues could be a sign that a child has processing or communication needs says Sue White, former teacher, SENDCo, education advisor to local government and a senior educational specialist at Widgit.

It’s Thursday afternoon and your pupils are returning to the classroom following an hour of playtime. After allowing a few minutes for the children to settle down, you start to teach an exciting geography lesson you have planned on climate change.

Halfway through your explanation of the learning objectives, a couple of children start talking, looking out of the window and disrupting their classmates. You might put the school behaviour policy in place, giving the children a verbal prompt to re-focus on the lesson, but they continue to be disengaged.

Are the pupils being intentionally disruptive or could there be another reason for their behaviour?

A recent study from the Education Endowment Foundation has reported that 76% of students starting school in 2020 required more speech and language support than in previous years. This coupled with the remote learning and lack of socialisation during lockdowns could potentially have contributed further to gaps in language development – meaning a vital skill to access learning is missing.

So, what can teachers do to tackle classroom disruption and help pupils with a limited vocabulary to fully engage in the learning opportunities being provided?

Make written and spoken words permanent

For some children, spoken instructions are not enough to fully grasp what is expected of them. Words become like air – once they are spoken, they’re gone. This makes it difficult for children with delayed processing or restricted vocabulary to know what they are supposed to be doing or learn effectively.

Visual prompts that represent the spoken word do not disappear and could help schools support pupils with communication difficulties to understand the structure of a lesson and navigate new learning opportunities and unfamiliar situations.

Asking a class to put their belongings away after lunch by holding up or pointing to a symbol of a coat, peg and a bag is a lot easier for a child with vocabulary gaps to follow than spoken instruction delivered in a busy classroom environment.

When coupled with spoken language, visual aids in the form of symbols help children concentrate on the information that matters without confusing them with unnecessary detail.

Here are two examples of how using visual symbols can support children and young people to engage in learning and help teachers reduce the likelihood of lesson disruption.

Set expectations visually

One relatively simple approach you can take is to add visual cues to the posters and signs displayed on walls, in corridors and in playgrounds that reinforce the school’s ethos and values.

This small step will help to make the school’s expectations crystal clear for children who have gaps in their vocabulary and enable them to play a full and active role in the school community.

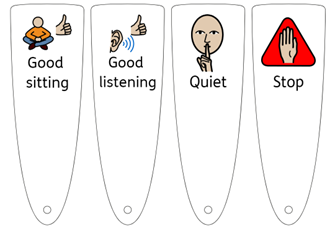

But symbols don’t have to be static resources. A teacher could create a set of hand-held images too, which can simply be held up during a lesson to praise a class for sitting still without stopping what they are doing. With a set of symbols to hand, a teacher could raise a stop sign to remind a child to refrain from talking without drawing additional attention to the situation or disrupting the flow of the lesson.

Expressing emotions

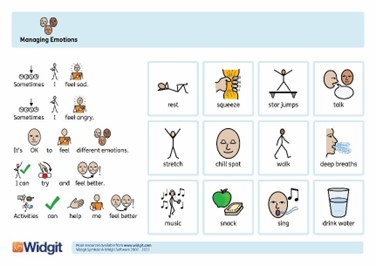

A child who feels frightened or upset is unlikely to be able to access the high-level thinking skills required to take on new information. As incredible as teachers are, they cannot read children’s minds – so having a visual emotion chart children can use to explain their feelings without having to verbalise them can really help give context to challenging behaviours.

If a child comes to school angry about an argument they had in the playground, they could simply point to an angry face on their emotion chart or hand their teacher a relevant card. This way, they do not have the added stress of having to articulate how they feel. The teacher can then quickly get a better understanding of the situation and help.

Visual charts can also help children to learn self-calming techniques. Having a quiet area in the classroom where a pupil can digest symbols to represent coping strategies like counting to ten, moving themselves to an agreed safe space, or deep breathing can quickly diffuse a highly charged situation and improve self-esteem.

Create a happy and productive learning environment

Making the school day more visual eliminates the need for children to process and interpret written or verbal information quickly. Amongst the hustle and bustle of the classroom, symbols remain a constant visual reminder of the words and phrases a pupil with limited vocabulary may not otherwise be able to retain. This can be an effective way to reduce classroom disruption and create a happy and productive place in which every child can learn.

Sue White is a senior educational specialist at Widgit and co-author of Walking the talk: A vocabulary recovery plan for primary schools.

Events

The Annual Health and Wellbeing in the Workplace Conference 2026

12 February 2026

The Future of UK Immigration 2026

26 February 2026

The National Operating Theatres Show 2026

10 March 2026

The Annual Facilities Management in the Public Sector Show 2026

17 March 2026

The Future of Academies Show and Exhibition 2026

25 March 2026

Courses

Neurodiversity in the Workplace

13 February 2026

10 spaces available

Leaders in Construction Programme - CMI Level 7

24 February 2026

7 spaces available

AI for Leaders

24 February 2026

7 spaces available

Women In Leadership

6 March 2026

6 spaces available

Construction Leadership and Management Development Programme - CMI Level 5

10 March 2026

6 spaces available